An illustrated rivalry

How the freemasons used the frontispiece in their rulebookSetting The Stage

During the 18th century, there were two rival Grand Lodges. Each lodge used the artwork in their books of rules (known as constitutions) as propaganda tools to promote their approach to freemasonry. These illustrations, or frontispieces, were often created by famous artists and many were sold as artworks in their own right. Each frontispiece is a valuable historical record, offering a unique insight into the lives of its creators and the state of English freemasonry at the time.

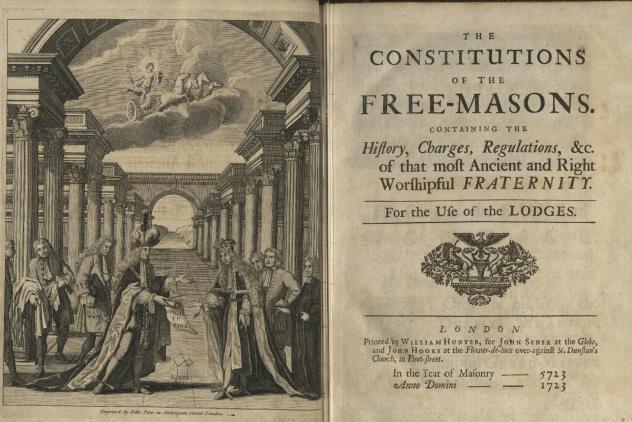

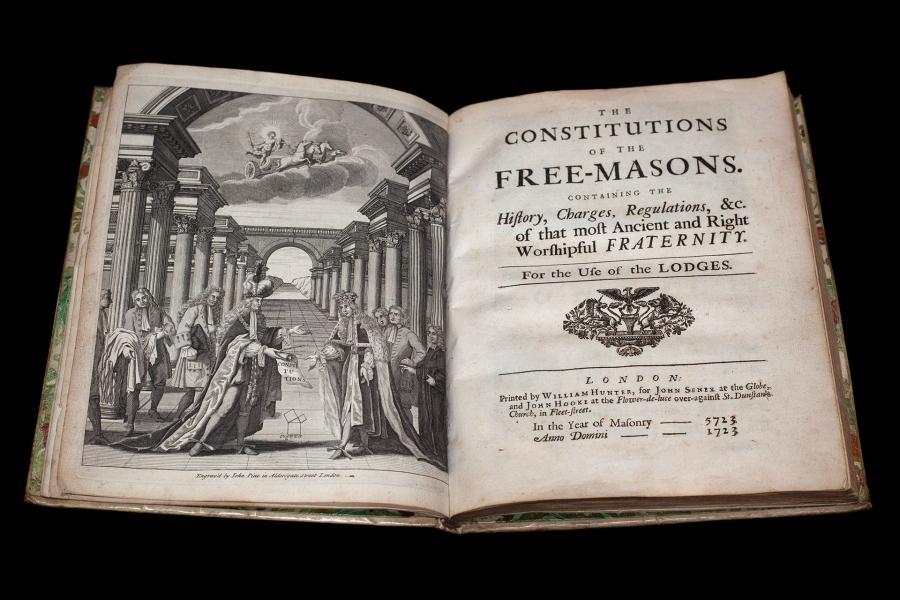

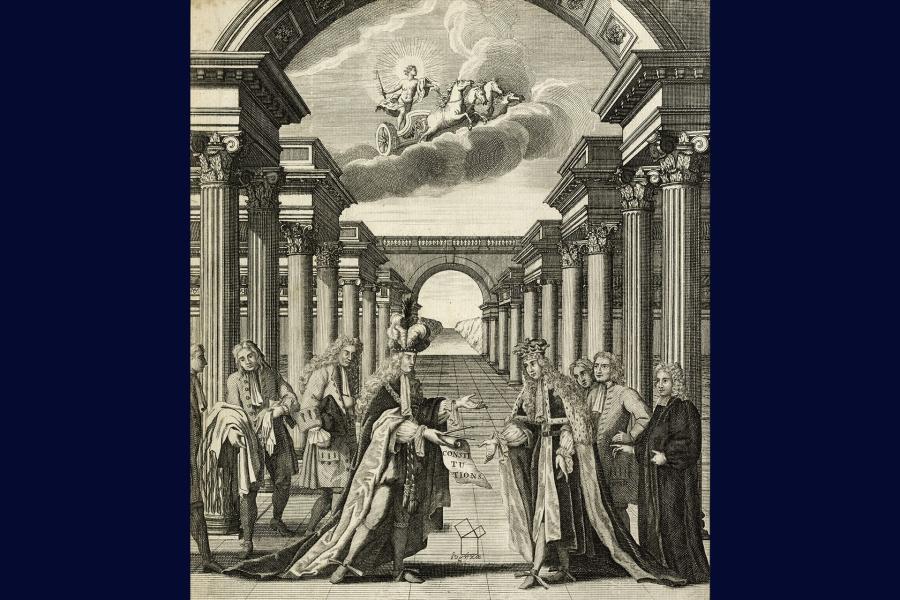

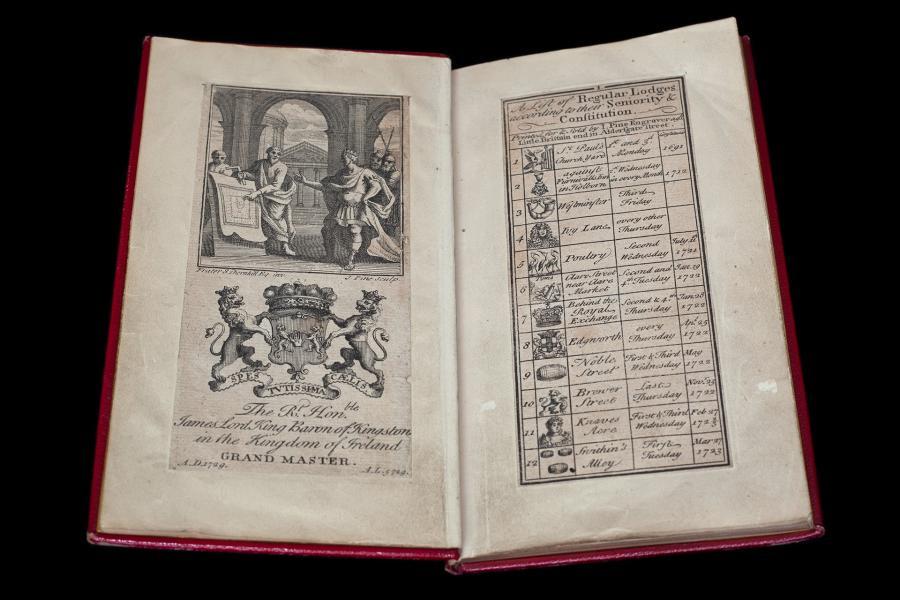

From Hand To Hand

Published for the original Grand Lodge in 1723, the first ever Constitutions was written by a priest called James Anderson. With the help of a frontispiece by engraver John Pine, it established the Grand Lodge as the governing body of English freemasonry. During this time, freemasonry evolved into an important and respected organisation. Pine engraved the Duke of Montagu, Grand Master in 1721, handing over a copy of the Constitutions to his successor, the Duke of Wharton.

Meeting Places And Speculation

Pine also produced lists of lodges so freemasons knew which taverns and coffee houses to meet at and when. These lists, essentially short guidebooks, were passed from man to man. This frontispiece is based on a design by Sir James Thornhill, who painted the inside of the dome of St Paul’s. Pine worked with both Thornhill and his son-in-law, William Hogarth, leading to speculation that one of them designed the frontispiece of the Constitutions.

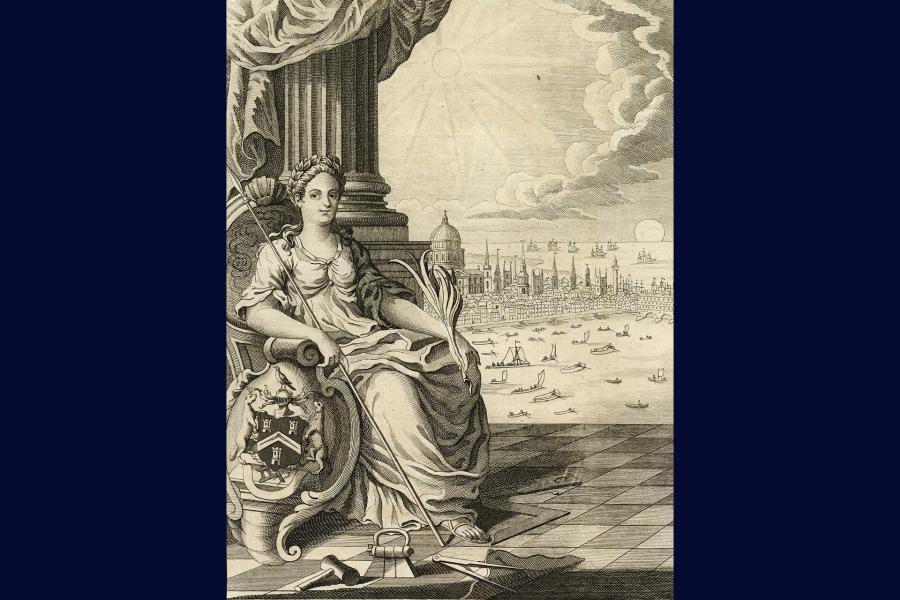

Patriotic Views

By the 1750s, the original Constitutions was out of date and a new book was commissioned in 1756. This frontispiece was created by engraver Benjamin Cole and Louis-Philippe Boitard, a French artist who was well known for his skillfully executed sketches of London life. It’s no surprise that Boitard produced such a patriotic frontispiece: 1756 was the year Britain entered The Seven Years’ War, a global conflict that established a new balance of power in Europe.

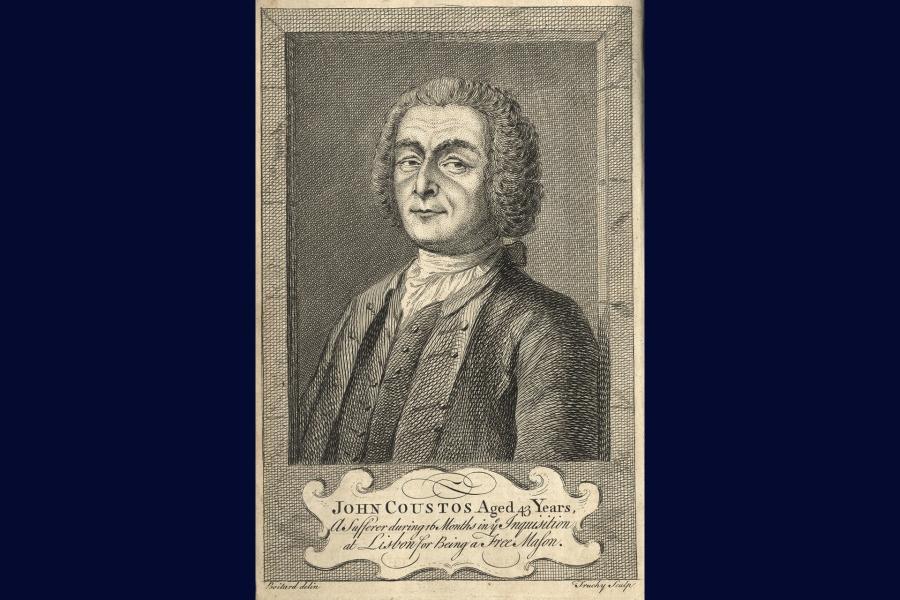

A Dark Chapter

Boitard was a Huguenot Protestant and lifelong freemason. In 1746, he illustrated The Sufferings of John Coustos, an account of a freemason’s imprisonment and torture by the Inquisition in Lisbon. Coustos, at one time allegedly a spy for British Whig Prime Minister, Robert Walpole, was arrested by the Portuguese Inquisition while travelling on business. The Inquisition and its fallout was a dark chapter in the struggle between Catholicism and freemasonry.

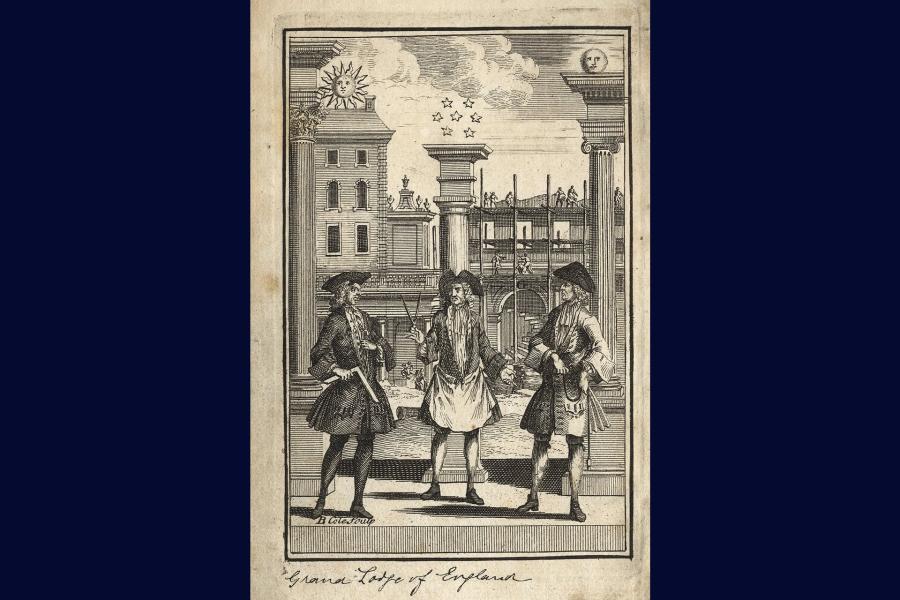

A Man Of Many Talents

Benjamin Cole was a man of many talents. As well as being an expert engraver, he was a surveyor, cartographer, instrument maker and bookbinder. In 1729, Cole printed and sold an unofficial version of the Constitutions for which he engraved this frontispiece of gentlemen masons in front of a new construction. He later replaced John Pine as official engraver of the Grand Lodge. Cole started a dynasty of engravers to the freemasons: two sons and a grandson followed in his footsteps.

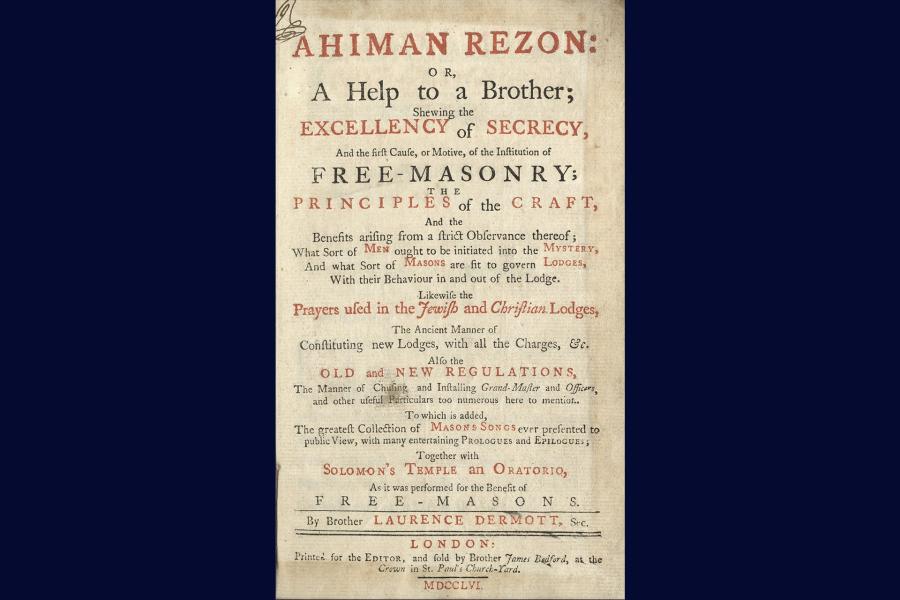

The Rivalry Begins

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Irish and Scottish freemasons in London didn’t hold to the beliefs and practices of English freemasons. They established a separate Grand Lodge in 1751 and published their own constitutions, Ahiman Rezon, in 1756. The name Ahiman Rezon is said to be derived from Hebrew but its meaning is unclear. The Antients (Ancients), as they quickly became known, believed themselves to be part of an older masonic tradition and criticised their rivals for modern innovations.

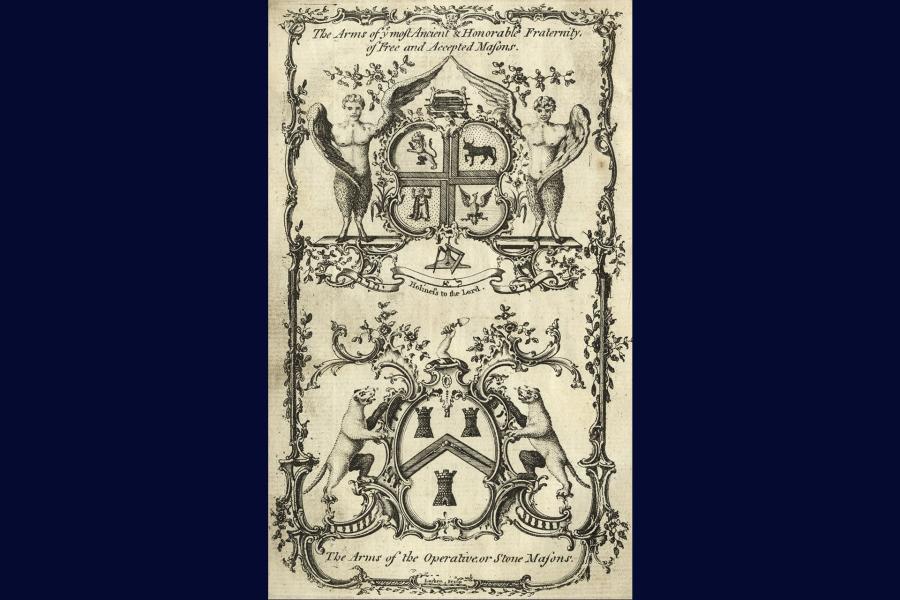

Convenient To Say The Least

The Antients’ Grand Secretary, Laurence Dermott, compiled the original Ahiman Rezon, and for the next edition in 1764 he designed this frontispiece with the engraver Patrick Larkin. Dermott described it as a depiction of his Grand Lodge’s coat of arms, which he believed was the coat of arms of the stonemasons who built Solomon’s Temple many centuries earlier. As this was, conveniently, also the coat of arms of The Moderns, it allowed Dermott to accuse his rivals of appropriation.

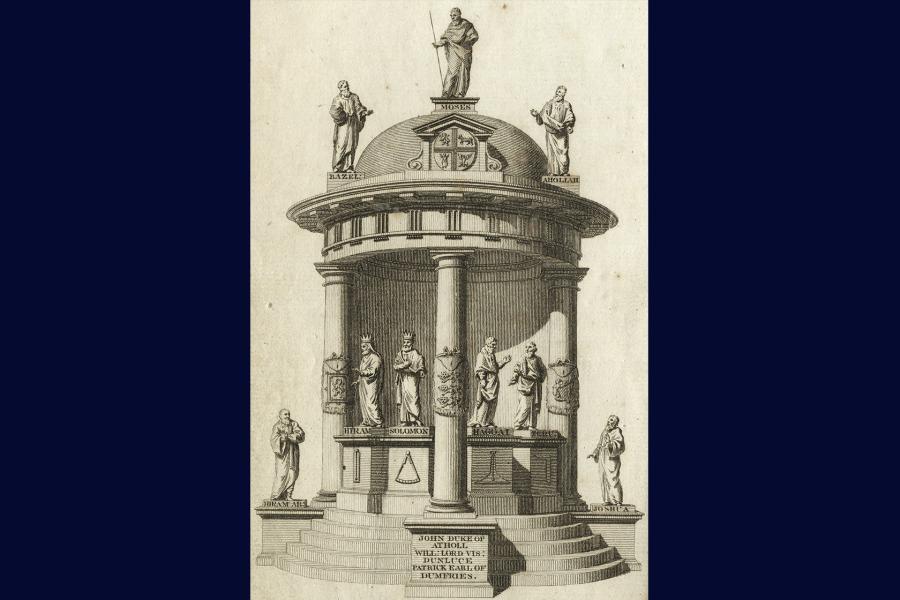

Ancient Links

Six further editions of Ahiman Rezon carried versions of this frontispiece, first used by Dermott in 1778. Here freemasonry is represented as a temple decorated with images of biblical patriarchs. Specifically, the master stonemasons who oversaw the construction of the Tabernacle in the Wilderness, Solomon’s Temple and the Second Temple. It also features stonemasons’ tools and aprons bearing coats of arms of England, Scotland and Ireland. This is overt propaganda, playing up the link between Dermott’s Grand Lodge and those in Scotland and Ireland.

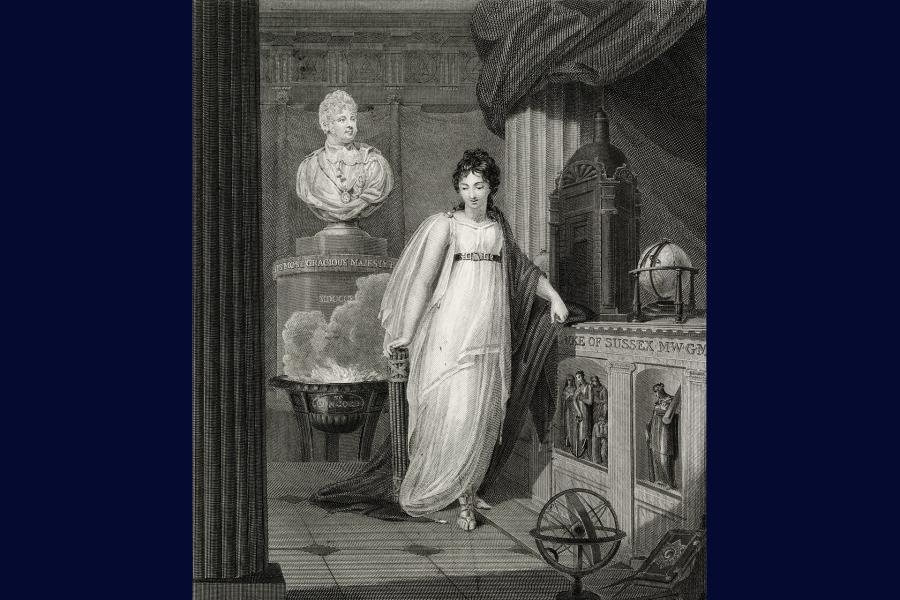

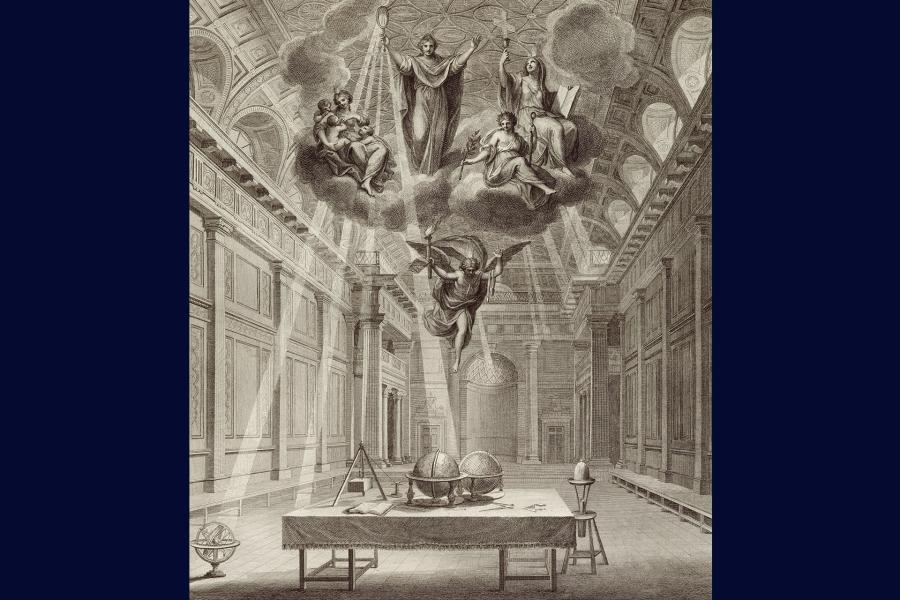

The Grand Architect

In 1776, the original Grand Lodge opened the first Freemasons’ Hall in London. The hall’s creator, self-taught draughtsman Thomas Sandby, was hailed by freemasons as the ‘Grand Architect’. Working with painter Giovanni Cipriani and engravers Bartolozzi and Fittler, Sandby created a frontispiece for the 1784 Constitutions. His design shows Faith, Hope, Charity and Truth floating in Freemasons’ Hall. Another figure, representing freemasonry, swoops down towards the foreground, which is covered with scientific instruments and stonemasons’ tools.

The Flourishing Arts

Florentine artists Cipriani and Bartolozzi were both members of the artistic and musical Lodge Of The Nine Muses in London. They created this design for a series of concerts held at Freemasons’ Hall in 1783. Both men were also founder members of the Royal Academy of Arts, as was Thomas Sandby and his brother, Paul. The Royal Academy of Arts was founded by King George III to promote the arts in Britain. There were 34 founding members in total.

The Grand Union

The rivalry of The Antients and Moderns came to an end in 1813 when the two Grand Lodges formed the United Grand Lodge of England. The first Constitutions published by the United Grand Lodge featured a frontispiece by the engraver Richard Silvester. With freemasonry as a female figure once again, the design celebrates the unification. Her belt is fastened with a handshake and she carries a fasces, or bundle of sticks, representing strength in unity. A new chapter of freemasonry had begun.