I’ve often heard the museum’s collections described as ‘quirky’. As an archivist, I’m used to seeing a lot of paper records, most of which don’t really fit that description. There are however, a few notable exceptions, an example of which features in our latest rotation of our ‘Treasures’ display.

The item in question is a manuscript volume, containing painstakingly researched notes and intricate illustrations, compiled by eighteenth-century freemason William Stukeley. He had trained as a doctor and kept up his interest in science through a passion for all things antiquarian. He was instrumental in the revival of the Society of Antiquaries in 1717, serving as its’ Secretary for nine years and he is regarded as one of the earliest ‘learned men’ to become interested in freemasonry, counting Sir Isaac Newton among his circle of friends.

We know about his freemasonry from his diaries housed in Oxford’s Bodleian Library. He records being initiated at a lodge meeting at the Salutation Tavern, Tavistock Street, London in January 1721. He went on to note that he was made Master of a new lodge meeting at the Fountain Tavern in the Strand on 27th December 1721.

His diary also talks about being present at the installation of John, Duke of Montagu as Grand Master, a key moment is the history of freemasonry. Montagu is a fascinating character all of his own and you can find out more about him in our online talk and in our upcoming exhibition 'Inventing the Future.

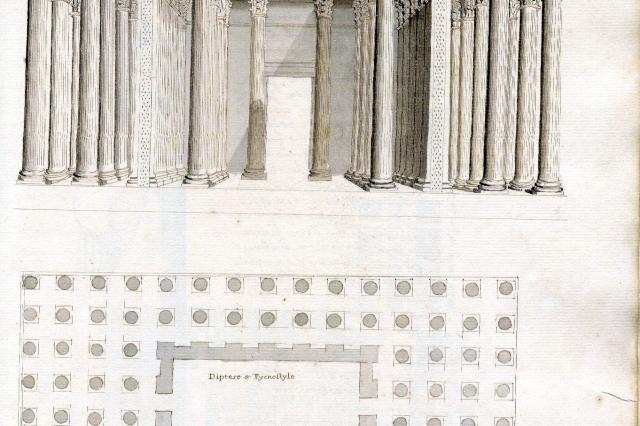

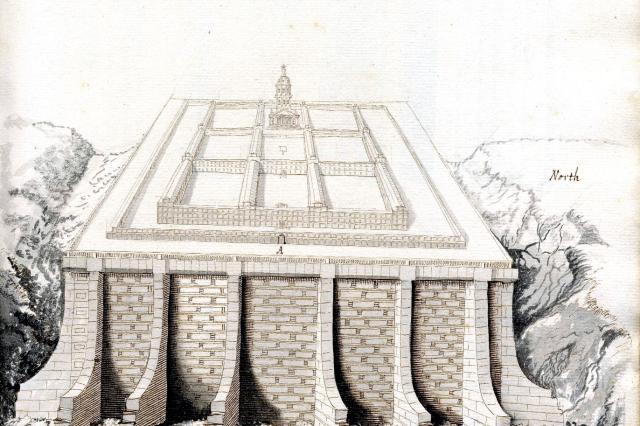

So, having explored Stukeley’s freemasonry, it’s time to delve a little deeper into the manuscripts he left behind. There are a number of these in our collection, covering a rather eclectic array of subjects. Topics include Stonehenge (Stukeley was particularly interested in links between freemasonry and Druidism), Solomon’s Temple, Egypt, Greek Gods and Biblical figures. The manuscripts were gifted to the Museum in 1924 by Edmund Hunt Dring, Managing Director of Bernard Quaritch Ltd, the famous dealers of rare books.

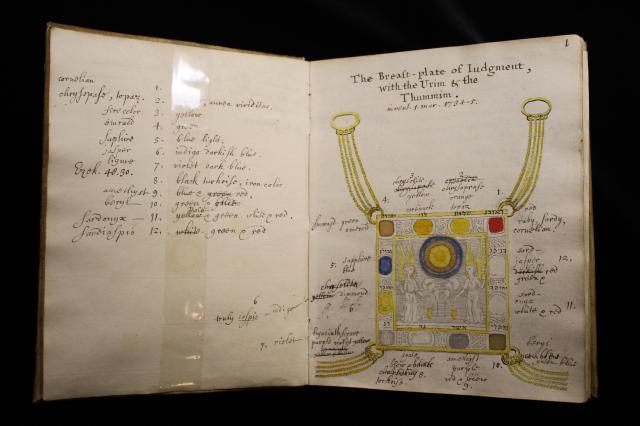

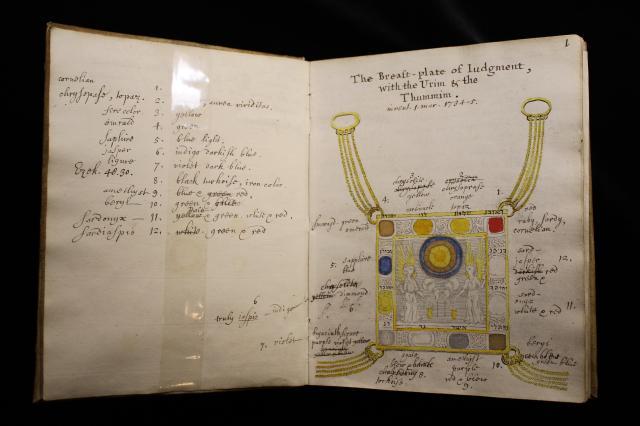

The volumes are all in Stukeley’s hand and are full of his own illustrations, including a representation of Aaron’s Breastplate. The illustration takes its inspiration from the Bible, with twelve jewels pictured representing the twelve tribes of Israel.

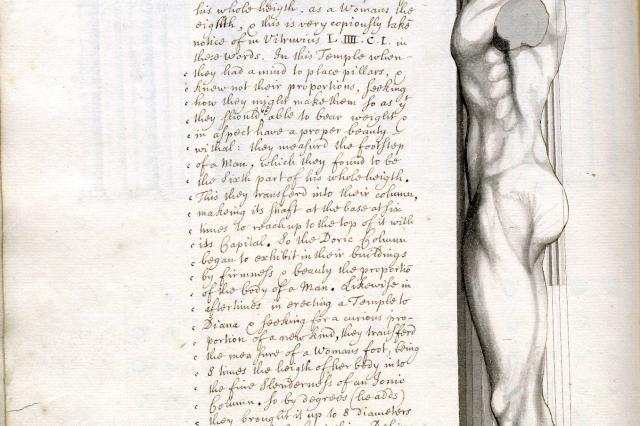

Although clearly an accomplished draughtsman (Stukeley was particularly fond of drawing scientific instruments and architectural details), his volume on depictions of Gods and Biblical figures does indicate that his illustrations of people were less successful. These small touches really bring home to me why these volumes truly are treasures.

These are not professionally bound volumes intended for public consumption. Instead, they are roughly bound in whatever was on hand, be that vellum as is the case here, or sometimes, even wallpaper, which just adds to their charm. Although the volumes all have general themes, the content is not organised in the traditional sense. Passages have seemingly tumbled onto the page, straight out of Stukeley’s head, suggesting that these were works in progress.

To me, that is what makes them so special. I think it’s fair to say that these were not supposed to survive beyond the lifetime of the man who created them. The fact that they have, and are still here for us to marvel at today, makes them something special. ‘Treasures’ is open in the Museum’s Library until December 2022.