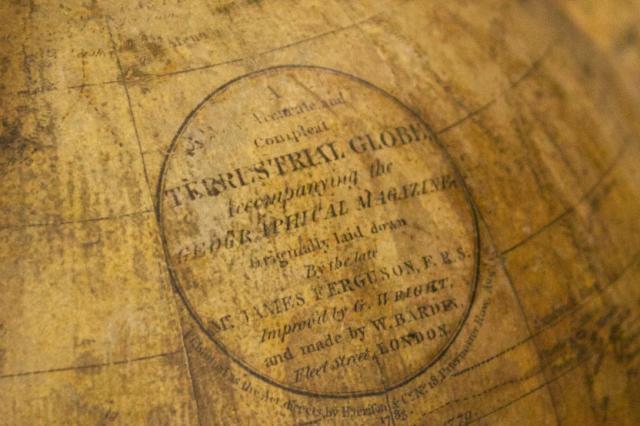

New information about the terrestrial and celestial globes in the Museum of Freemasonry’s collection has come to light while working on the Inventing the Future exhibition. Items such as the globes, on display in our South Gallery, reveal how freemasons embraced Enlightenment thought, stimulated by a search for knowledge through new scientific methods and rational observation. The race to explore the world encouraged the map maker, William Bardin (c.1740–1798) to include an inscription to Sir Joseph Banks, freemason and President of the Royal Society on the terrestrial globe.

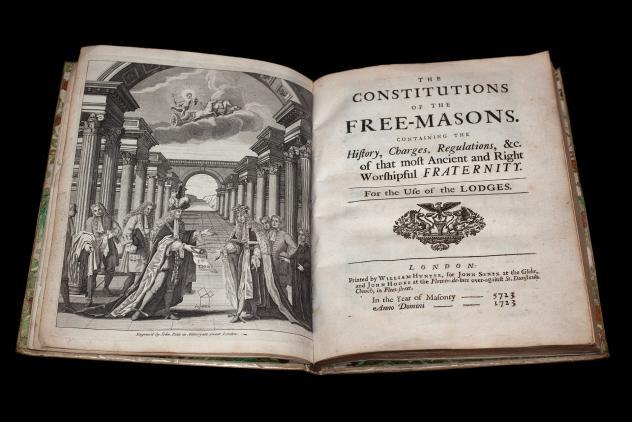

Bardin and his collaborator, Gabriel Wright made these globes in London’s Fleet Street in 1785. The pair started to produce these luxury items in the 1780s, based on designs by John Senex (1648–1740), the father of British globe making and co-publisher of the Book of Constitutions. Senex dominated the early eighteenth-century globe-making business, which his widow Mary continued after his death. Wright was a former employee of Benjamin Martin (1705–1782), whose company acquired Senex’s globe printing plates.

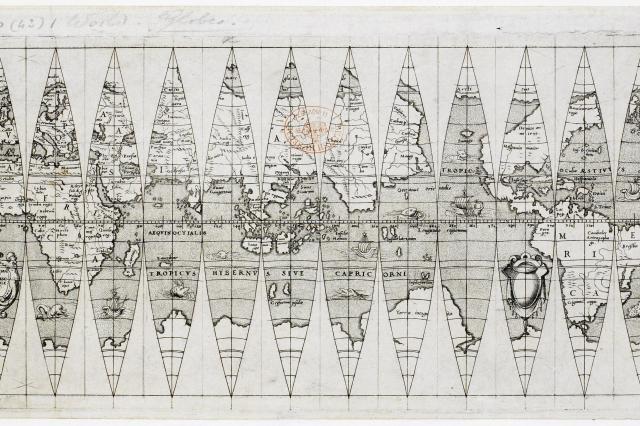

Manufacturing printed globes remained remarkably similar for over two centuries. First, two half-hemisphere shells were formed from papier mâché or layers of paper. Once dried and removed from the moulds, a wooden rod connected the two shells through holes at the north and south poles. The shells were then sewn or glued together and sealed with more paper or a cloth strip.

This formed a paper ball, which was coated in plaster. The gores, or printed segmented maps, were pasted onto the plastered surface to make the globes, each segment forming a single gore. It was difficult to ensure a smooth surface and this skilful job involved stretching the prints onto the spheres. Allowances for this were needed when engraving the terrestrial and celestial maps.

The first globes produced by Wright and Bardin, with diameters of 9 and 12 inches, were produced in 1782. Although the cartography is similar, some versions include a label announcing the pair’s improvements located in the North Pacific Ocean of the terrestrial globe. As this label claims, in 1783 Wright published a book explaining his innovations. He printed hour circles onto the globes around the poles, printed the hours around the equator and included small brass pointers between the globe surface and the meridian ring. In consequence the globes could be inverted on stands, without the hindrance of a brass hour circle attached to the meridian.

This pair are sometimes referred to as ‘Free Globes’ and were a clever marketing ploy used by Harrison & Co to launch a monthly serial, The Geographical Magazine; Or a New Copious, Compleat and Universal System of Geography. Readers who signed up to receive the new publication in 1782 were entitled to a free pair of globes. Subscribers received a terrestrial globe after the twentieth edition and a celestial globe after the fortieth edition.

Wright and Bardin’s partnership lasted only a short time, which suggests possible business problems. However William Bardin and his family continued as leading globe manufacturers well into the 19th century.

Find out more about these globes and their place in history in our new exhibition, Inventing the Future.