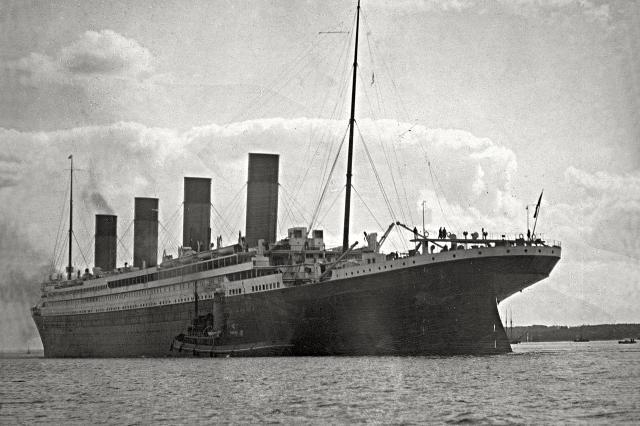

Who hasn’t heard of the Titanic? The tragic story of the ship that struck an iceberg and sank on her maiden voyage is so well known that it was made into a Hollywood blockbuster. So, imagine my surprise when I discovered a link to this piece of history buried in the Museum’s archives. I was looking for items for our Treasures exhibition in 2019/20 and it was chance to show off areas of the collections which people don’t often get to see. I stumbled across the words ‘Titanic case’ written in red ink across some of our records.

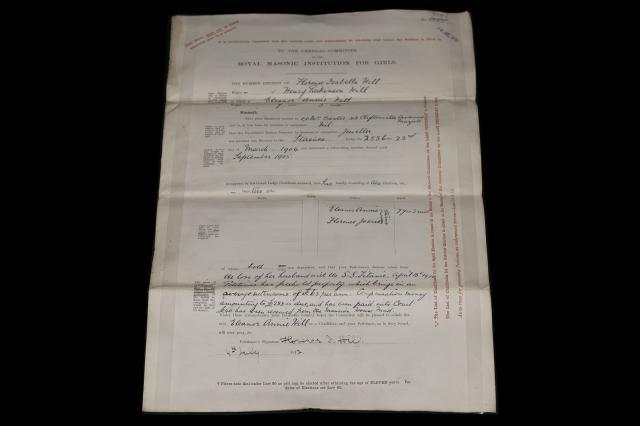

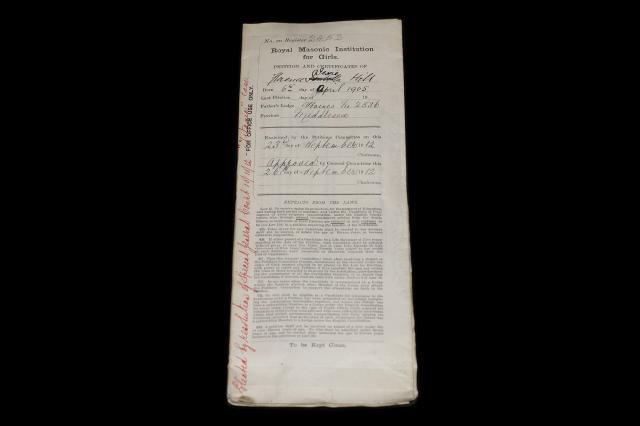

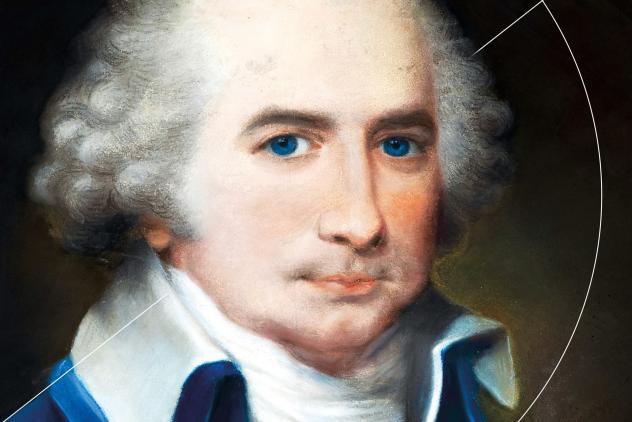

I was looking at items relating to the Royal Masonic Institution for Girls. This was a school set up by freemasons, led by Bartholomew Ruspini in 1788 to support the daughters of members who had hit hard times. Often, fathers had died, leaving mothers without a means of supporting their children. To apply for a place at the school, an application was completed, known as a petition. Our Archives include petitions going back to 1789 and they are, quite possibly, my favourite part of the collection.

The records of the School for Girls are mostly made up of minute books, admissions registers and petition paperwork. The forms give rather dry details of finances, along with the copies of birth, marriage and death certificates, and medical officers’ reports. They only tell half the story. Amongst the impersonal facts and figures are letters written by friends of the families, doctor’s notes, and even samples of children’s handwriting. As well as giving details of a father’s freemasonry, these records are a window into the human stories behind the paperwork.

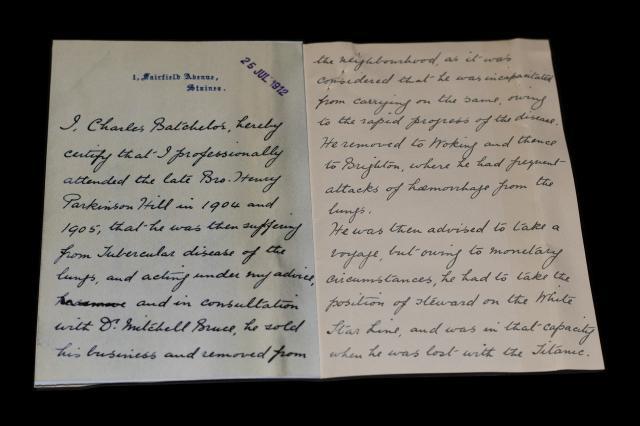

The case of seven-year-old twins Eleanor and Florence Hill is particularly poignant. Their father, Henry was a freemason, initiated in Staines Lodge in Middlesex in March 1904 and had originally worked as a jeweller. The girls’ petitions for admission include a letter from the family doctor, Charles Batchelor, concerning Henry’s health. He had been suffering from ‘tubercular disease of the lungs’ and had given up his business and moved to Brighton in the hopes of improving things.

Mr Batchelor’s letter goes on to say that Henry had also been ‘advised to take a voyage for his health’. Unable to afford a ticket for a voyage, and in a rather tragic twist of fate, Henry instead took a job for the White Star Line. By that point he had moved to Southampton, working as a Steward on the Olympic before boarding the Titanic on 4 April 1912. The letter rather blandly ends with the statement that Henry was ‘in that capacity (as a Steward) when he was lost with the Titanic’. Without her husband’s income, his widow Florence was unable to support her daughters and called on the freemasons for help.

Stories like this are the reason I became an archivist. There is something about handwritten pages that transports you into the lives of the people who wrote them. When looking at the school records in particular, I find myself wondering what happened to the families who needed help – what were their lives like? From these records we get a glimpse of Henry’s life before the Titanic and the unfortunate circumstances which led to him being on the ship on that fateful day. These pieces of paper in the Museum’s Archives make him, and his family, all the more real and, to me, that’s what makes them a true treasure.

Our Library and Archives are full of these human stories, waiting to be discovered. Unearth your own treasures by visiting the Museum or registering as a reader to discover your own hidden gems in our collection.